Jeffrey01-Title

Jeffrey01-Title

News of the world, in three acts: a dispatch from Australia

Jeffrey01-Text

Jeffrey01-Text

Note: The author has included Wikipedia references (linked in the text) as they provide easy access to further information, which appears, when checked against other less easily accessed sources, reliable for the contexts addressed below.

The Daily Colonist was started in 1858 in a trading settlement, founded fifteen years earlier, on the southern tip of Vancouver Island on Canada’s far west coast. By 1888, as the new trans-Canada railway began to bring settlers from the east, Victoria had a population of about ten thousand that would grow to twenty thousand by 1900.

The Age in Melbourne, the capital of the colony of Victoria in Australia, was of similar vintage, founded in 1854. Melbourne, like Victoria, BC, dated from a settlement of Europeans in 1835. (There were flourishing societies in south-eastern Australia and on the west coast of Canada long before the arrival of Europeans).

By 1888, Melbourne was at the peak of its ‘marvellous’ period, one of the most prosperous cities in the world, funded from the proceeds of an earlier gold rush and the growing shipping capacity that carried grain and wool around the world. Its population was 300,000 – thirty times that of Victoria, BC.

The Times of India claimed its origins from the year 1835, but the name on the masthead became The Times of India only in 1861. Bombay was entering a period of economic boom, accelerated by the American civil war and the vastly increased value of Indian cotton, along with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

▲ THE DAILY COLONIST 10 March 1888. Digitised copies of The Colonist can be seen here. (Image courtesy of University of Victoria Libraries, British Columbia)

The striking contrast with today is how relatively easy it was to start a newspaper in the mid-nineteenth century, as the careers of the founders of these three publications illustrate. All three were migrants, classic examples of how Britain’s empire enabled poor young men to get on in the world. They made their names, and died, far from their birthplaces.

David Syme (1827–1908) of The Age was the most successful in commercial terms. Born in Scotland, he had his first job in a print shop, but was drawn by two gold rushes, first to California in 1852 and from there, to the gold rush in the colony of Victoria in Australia. (Among many things Queen Victoria has to answer for is that 120 years after her death, there are far too many places still named after her.) With a relatively small stake, Syme was able to take over the fledgling Age a year or two later. He became a powerful force in the politics of the colony of Victoria, and bequeathed the newspaper to his sons on his death. The family continued to own the paper until 1983. [See: David Syme (Wikipedia)]

Like Syme, Amor de Cosmos (1825–1897), born Alexander Smith in Nova Scotia in eastern Canada, was also drawn to the California gold rush. While he didn’t make a fortune, he made money taking photographs (daguerreotypes) before heading north to Victoria, BC. He founded The Colonist in 1858 in the middle of the British Columbia gold rush, had a brief stint as premier of the province and was declared insane in 1895. [See: Amor De Cosmos (Wikipedia)]

Robert Knight (1825–90) was born in London, one of nine children (he had eleven of his own), and was packed off to India as a clerk. After a precarious career in commerce, he found himself editing an Indian-owned newspaper in Bombay. He eventually bought it and re-named it The Times of India in 1861. He died in Calcutta where he had founded another important daily, The Statesman. [For more details: Edwin Hirschmann, Robert Knight: reforming editor in Victorian India (Oxford University Press, 2008)]

All three began as young men on the make, looking for ways to make their fortunes. Gold, tempting for two of them, proved unrewarding. The ‘start-up’ that worked, for influence if not great wealth, was a newspaper. To start a newspaper in a corner of the British empire in the mid-nineteenth century was a better bet than looking for gold. Even the Australian adventurer John Lang’s account of setting up a newspaper in Meerut in the late 1840s demonstrated that if you could find brandy for the proof-readers and a tombstone for a layout table, financial success was possible.

The ‘business plan’ of course required a selling price for the newspaper, but that was not the main game. In 1888, the masthead of The Age announced the cost of a copy was a single penny (sterling) or 1/240th of a pound. For that, you got a newspaper that ran to sixteen pages on Saturday, and twelve on other days. By 1900, The Age was selling about 120,000 copies a day.

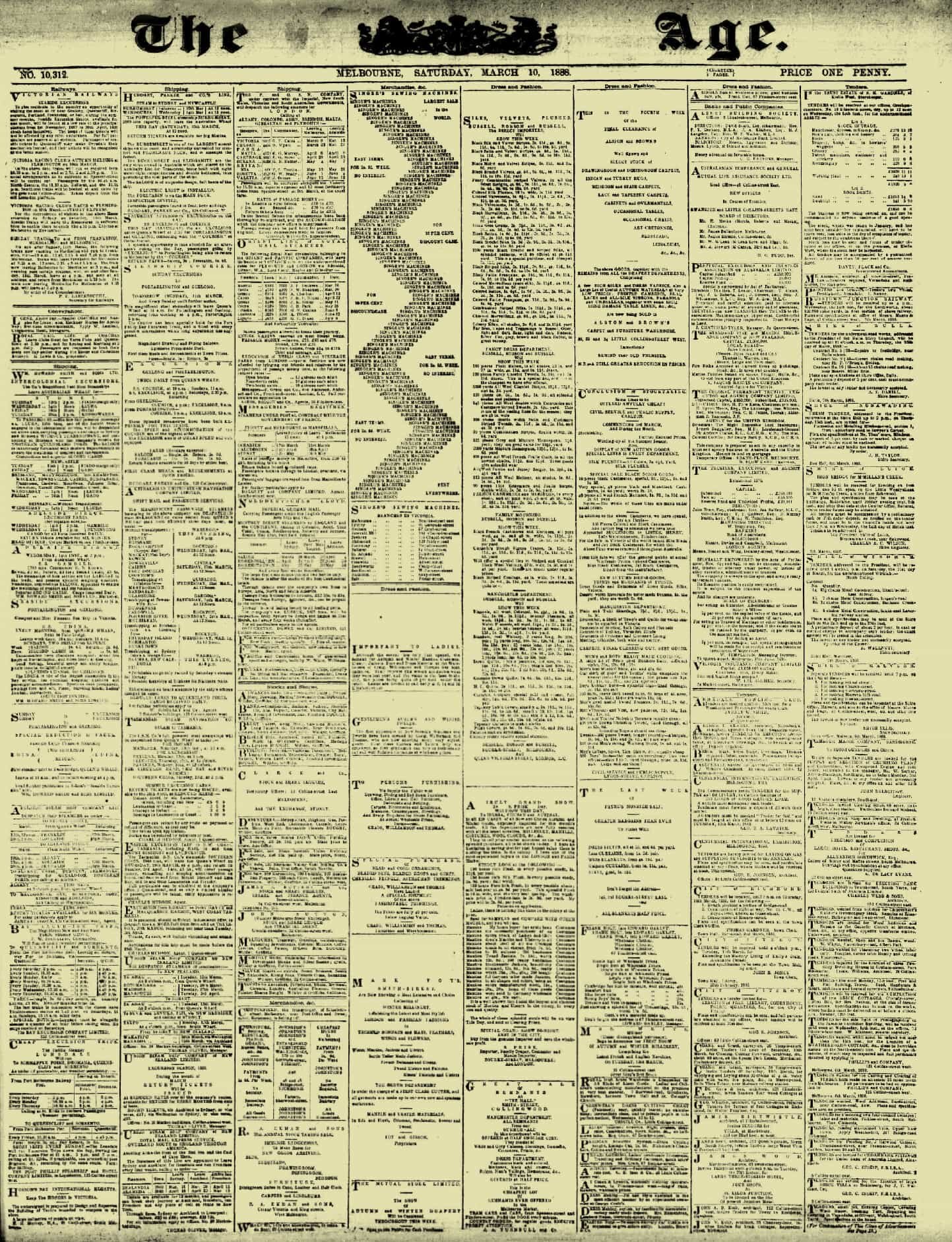

Melbourne in the 1880s was one of the wealthiest cities in the world, and the 10 March 1888 edition of The Age offered eighteen pages, twelve of them devoted to mouth-watering advertising – mouth-watering at least for David Syme. The Age fed off these ‘rivers of gold’ for the next hundred years.

▲ THE AGE 10 March 1888. Digitised copies of The Age are part of the National Library of Australia’s Trove Project which has digitized dozens of Australian newspapers: see here. (Image courtesy of National Library of Australia, Canberra)

The Times of India had a much smaller market of British civil servants, soldiers and business people and Indians in commerce, education or government service. It had a higher selling price than The Age. Its weekly edition was four annas, or a quarter of a rupee, at a time when an Indian school teacher might have been paid eight rupees a month. It sold about 3,000 copies a day in 1890.

The masthead of The Colonist in tiny Victoria, BC, reminded readers what the newspaper industry rested on. The Colonist had ‘Double the Circulation of any other Paper in the Province’ and therefore was ‘unexcelled as an advertising medium’. British Columbia doubled in population between 1880 and 1890 to about 100,000 people, and Victoria was the biggest town. The Colonist gave readers four pages a day for five Canadian cents, and its circulation by 1888 may have reached 2,000 copies. Its first print run in 1858 had been 200. [See more: here and here)

Advertising was the essence of all three businesses, as it had been for most dailies since the first appeared in Europe in the 1600s. On 10 March 1888, The Times of India and The Age devoted their front pages entirely to advertisements. (The Times of London did not put news on the front page until 3 May 1966.) The four-page Colonist had news on every page and was 60 per cent advertising.

But what about ‘news’? It travelled fast in 1888. On 10 March, the death of the German emperor topped the Colonist front page. However, ‘THE KAISER DEAD’ was in a font half the size of the advertisement next to it for Canada’s corporate octopus, the ‘Hudson’s Bay Company’ and its announcement of ‘FRESH SUPPLIES’. The Colonist loftily claimed its despatch about the emperor’s death, dated 9 March, Berlin, was ‘Special to the Colonist’. It also offered readers front-page variety: crime (‘SNELL’S MURDER’), politics from Britain, sports (‘THE SULLIVAN MITCHELL FIGHT’) and a healthy dose of ‘LOCAL BRIEFS’ and ‘POLICE COURT’.

In Melbourne, The Age had ‘DEATH OF THE EMPEROR WILLIAM’ on page 11, a three-line bulletin ‘by submarine cable’ coming ‘from our own correspondent’, datelined London, 10:50 am on 9 March. A muddy engraving of the late emperor glowered above two columns, anticipating the emperor’s death and describing his reign.

▲ THE AGE 10 March 1888, with the engraving of Kaiser Wilhelm I appearing on page 11. (Image courtesy of National Library of Australia, Canberra)

At The Age, the death highlighted two aspects of change in the newspaper business. Australia had been linked to London by cable, through India to Darwin, down to Adelaide, and then to Sydney and Melbourne, in 1871. News of a death in Europe in the early morning of 9 March 1888 reached Melbourne within minutes and therefore about 9 pm the same day, plenty of time to be included in the edition going to press for the morning of 10 March.

The type from which The Age was printed was still composed by hand. Ottmer Mergenthaler’s disruptive invention, the Linotype machine, had gone into service only two years earlier at The New York Tribune. By the early 1890s, however, The Age had introduced Linotype machines, speeded up production and shed most of its hand-composers. (David Syme was said to have looked after his unemployed compositors either through pensions or by finding them jobs).

The Times of India on 10 March carried a series of breathless ‘LATEST TELEGRAMS’. The first, dated London, 8 March, 1:50 pm, reported that the Emperor ‘passed a restless night’. The next at 7:25 pm reported ‘The Emperor of Germany is dead’, but at 9:55 this was corrected to be ‘premature’ and reported that ‘His Majesty has only swooned’. At 4:50 am on 9 March, he had experienced ‘a further improvement’. At 9:35 am came the message that ‘The Emperor of Germany died at 8:30 this morning’. Editors who manage the tickers on today’s TV news channels may recognise their predecessors.

The Times of India that Saturday carried eight pages with advertisements taking up about 60 percent of the paper. Indeed, advertisements provided the only illustrations: engravings of complex-looking machines, watches, boots, guns and tubs of ‘Oriental Tooth Paste’, among other things.

▲ THE TIMES OF INDIA 10 March 1888. Digitised copies of The Times of India are available through several major libraries. The author used the State Library Victoria, accessed here. (Image courtesy of State Library Victoria, Melbourne)

Were these three newspapers products of some sort of Golden Age of Journalism when fighting editors and reporters resolutely pursued truth in the interests of an informed public? No. There never was a Golden Age of Journalism when all reporters were hard-bitten, truth was the goal and newspapers the messenger. These three proprietors used their newspapers to get on in the world and to pursue their interests, which may sometimes have coincided with a larger good. All of them operated in British colonial possessions and took the part of locals, which sometimes brought conflict with authorities appointed from Britain.

Amor De Cosmos attacked the governor of the province of British Columbia and eventually served a brief term as premier. But he ended his days as a mad eccentric. When Robert Knight died, he got a critical obituary from his old newspaper, The Times of India, which concluded that ‘he preferred to be on the losing side, not so much from conviction as from the innate love of singularity’. Knight, however, had the satisfaction of passing to his sons The Statesman, the daily he founded in Calcutta, and in being celebrated in an Indian-owned daily as ‘the only English editor who devoted his life to the cause of the natives of this country’. (Edwin Hirschman, cited above: 235–236). David Syme of The Age died prosperous and powerful, the confidant and essential backer of politicians in the colony of Victoria (a state of Australia from 1901). But, he told a friend, ‘my business interests … absorb my attention. I’m different from you; I’m a man with few friends’. [See: here] And Syme’s influence extended largely to the state of Victoria, not to Australia as a whole.

Today, The Times of India under its successor company, Bennett Coleman Company Ltd (BCCL) is India’s largest media group – vast, dominant, very vulnerable to government pressure, and still controlled by a family (though not Robert Knight’s). The Statesman, a tough and admirable newspaper forty years ago, fades into obscurity in Kolkata. The Age, now merged with a television business, survives, and Melbourne, a city of five million, still has two daily newspapers. The Colonist, which merged with its evening rival in 1980 to form The Times-Colonist, struggles on in Victoria, BC as the largest old-fashioned newspaper in a Vancouver-based media group.

In 1888, all three newspapers and their founders were tightly connected to their localities and the commerce of their localities. Local advertising created the ‘rivers of gold’ for The Age, and enabled The Colonist to charge twenty cents a line for a classified advertisement and run a revenue-rich newspaper. Even Knight, much more dependent on an authoritarian imperial government, could cobble together just enough financial support to keep his papers running.

In today’s digital world, local advertisers no longer need newspapers to disseminate messages. Any fool can tweet, and more than their share do. Anyone with a phone, an inclination, and a broadband connection can write a blog or join a ‘news group’. The great ‘platforms’ of Facebook and Google can disseminate information (and harvest advertising) without having to pay for it on the pretence that they are simply trees on which anyone is free to tack a message.

While there was no Golden Age of Journalism, it is hard to imagine how rule of law and democratic government can get along without well-led local news-gathering, based on an ideal of truth-finding and supported by a viable business model. (News-gathering often needs lawyers and security behind it, and they cost money). De Cosmos, Knight, and Syme were not special exemplars of truth-telling, but they tangled with authority ‒ and authority had to reckon with them ‒ in ways impossible in centralized totalitarian regimes. They would have agreed with ‒ even if they didn’t always live up to ‒ the belief of the admirable American ‘muck-raker’ Ida Tarbell that ‘the Truth and motivations of powerful human beings could be discovered’. [See: Ida Tarbell (Wikipedia)]

And what of the dead emperor who was the big story on 10 March 1888? He wasn’t a fan of the press – he banned forty five socialist newspapers in the previous decade.

ROBIN JEFFREY is Visiting Research Professor at the Institute of South Asian Studies, Singapore. His most recent book, written with Assa Doron, is Waste of a nation: garbage and growth in India (Harvard University Press, 2018). He is the author, also with Assa Doron, of The great Indian phone book (Hurst, Harvard, and Hachette India, 2013). He has published numerous articles on newspapers and journalism in South Asia, and he is the author of India’s newspaper revolution: capitalism, politics and the Indian-language press 1977–1999 (Hurst, 2000). He lives most of the year in Melbourne.